Oiga, Vea!

on Top 10 lists, alternate film histories/canons and Chantal Akerman's 𝘏𝘢𝘯𝘨𝘪𝘯' 𝘖𝘶𝘵 𝘠𝘰𝘯𝘬𝘦𝘳𝘴...

THE CLICKBAIT VERSION OF THIS would have been called “Lists Are Bad.” (Maybe with the subhed “Here’s Why You Should Stop Making Them.”) And explaining why lists are bad seemed like a pretty simple task back when it was supposed to run, December 2022 (for reasons which will reveal themselves in short order.) I missed that window of opportunity, but managed to rationalize February, given the run-up to the Oscars. After that came March (the actual Oscars) and still nothing. My young coworker, dangerously privy to the breaking-down of these production timelines, started asking me: “Where’s the Substack?” Deadlines blown, brains ground to a fine dust, subscribers jumped ship, spring sprung; I even contemplated pulling the plug myself, putting my ideas into palliative care. Technically, right now is the worst time to publish, because the gap between the Oscars and Cannes - arguably the only interregnum separating the official end and unofficial beginning of “Awards Season” - just closed.

But I couldn’t bring myself to not-finish this volume of Element X. The process of wrangling these thoughts has taken not just months or years but, I realized, decades. The question of artistic “merit” haunts movie-maniac culture in ways large and small, some impossible to ignore, others invisible to the naked eye. I realized my problem isn’t with lists - which are, unto themselves, a film programmer’s best friend, the brainstorming being the most fun stage of almost any curatorial project - but rather with ranking. The rating and ranking of movies, the cataloguing of opinions, the sifting of taste: it’s ballooned into a… “industry” isn’t the word, but the rise of Letterboxd proves there’s data (and therefore money) to be mined from people’s - dependency? obsession? habit? - on chronicling their movie diets, breaking their responses to films down into numbers, stapling their kneejerk reactions upon the telephone poles of the much-ballyhooed “digital town square”. A lifetime ago, I tried participating in this kind of opinion-gathering on IMDB, then on a website called Flixster circa 2006/2007 and finally, briefly, on The Auteurs (now known as MUBI) before losing interest once and for all. Maybe these are the circumstances that pushed me into criticism: it sounds comically high-minded in retrospect, but I wanted my writing about movies to speak for itself.

I hated the idea of “objectivity” among critics: it was impossible not to grade on a curve, and therefore I saw my task as a critic to “describe the curve.” By far, my most prolific period reviewing movies was for the website Slant1, cofounded by Ed Gonzalez and Sal Cinquemani, notorious for their exacting rating system and hell-or-high-water rigorousness in the edit. Writing for Slant meant giving star ratings. So we would argue, email after email, over why I should award a film 2.5 stars when my review read more like a 3, or why it should receive a 3.5 when so many flaws were openly dragged into my assessment, et cetera2. A couple times, Rotten Tomatoes even reached out to clarify if one of my reviews had in fact been Fresh or Rotten. I wanted to do whatever I could to gum up their machinery: how could a subjective art experience be boiled down to one of these two ludicrous categories, to say nothing of a dumb number rating?

Anyway: this bygone winter I held my nose and joined Letterboxd, because the tea leaves said Twitter - my preferred means of arguing about movies online, at least when I signed up 10+ years ago - was going up in a puff of smoke. (Wishful thinking, as right now it’s looking more like a long, slow, weird, janky decline.) But I also joined Letterboxd because I wanted to see what, if anything, people were saying about movies I programmed. I had regarded the site with skepticism, and still do: it feels like the breeding ground for a certain cinephilia which could only have come around thanks to the angel/devil possibilities opened up by streaming and torrenting. The most zealous users are probably the same type who use (and, in some cases, post freely about using) semisecret torrent websites and thus, for whom, only a select few movies are truly impossible to see. Their level of access is neither fully privileged nor proletarian in effect; those who know, know, but that number remains relatively small in proportion to the world’s corpus of movie watchers, even as piracy grows more sophisticated all the time3.

So let’s say you’re a programmer, or work for a distributor: tracking a film’s activity via Letterboxd will help determine if a file has become suddenly available to a large number of people who, probably, do not live in the town where the film last screened. (In other words, the site encourages narc and pirate tendencies alike.) Or let’s say you’re a director: For all the shock I’ve feigned at filmmakers monitoring the responses to their movies on Letterboxd - don’t they have more important shit to do? - I’m not above admitting I have checked the site immediately after screenings I organized, and sometimes find the reviews, like this one of Ileana Pietrobruno’s Girl King (2002) published by “lex” after a screening I organized around this time a year ago, deeply moving.

Multiple friends warned me before I signed up: Letterboxd was a great place to broaden my horizons, stalk my audiences and, if I felt like it, to taxonomize my reactions - but horrible as a social media network. And indeed, more often than not, I’m finding that the top review of a movie on Letterboxd is the kind of pithy one-liner jerry-rigged to “do numbers” on Twitter during a major film festival. I’m complicit in this economy; I too have had the experience of sitting through a world premiere screening and spending the last seven-to-fifteen minutes of the movie concocting a glib 140-character verdict, aiming to splash as loudly among the peanut gallery before being forgotten forever. If I’m lucky. Did these experiences make me a better, or at least more a concise, writer? Maybe. Probably not. I can’t imagine they actually helped my thinking about cinema.

These are the wages of sin. Many things have happened to deprivilege the film critic-as-tastemaker; at the top of my personal list (ha) would be the explosion of unpaid writing about movies online, which has been a boon for self-expression and a blessing for formalist critical discourse… and/but a disaster for the idea, now quaint but totally reasonable less than twenty years ago, that writing about movies could be a viable way to eke out a living. On the “business” side, we’re living in a golden era of whatever results in quick and easy web traffic: lists and listicles, bogus headlines engineered to raise eyebrows, and the kind of kneejerk “hot take” I just described - the opposite of rigorous, but often successful inciting an afternoon’s worth of ersatz controversy on social media. (Just as it’s impossible to watch a film “ironically”, hate-clicks are still clicks.) In the last several years I have had an easier time trusting individual writers than outlets - knowing they are susceptible to the problems cited above if not to “restructuring”, “pivoting to video”, “pivoting to AI” (all bywords for layoffs) or just folding entirely.

Thus far, my use of the site has been touch-and-go, bracketed by weeks if not months of inactivity (imagine that!) But it only took about 90 seconds after logging on to realize Letterboxd is, of course, far more than a “film ranking website.” Users publish lists (numbered and otherwise) that help draw visibility to movies far afield of “the conversation”; the ease of self-publishing yields a bustling marketplace of takes, making the site an essential platform for criticism outside the norm. Letterboxd caters to an audience of obsessives and completists. Either term could describe a young cinephile ca. 2023, and Letterboxd genuinely seems like a great place to learn about new-to-you films. There is definitely a “Letterboxd mentality” which asserts itself in this abstracted digital space, where a film’s archival status or history of distribution/exhibition are immaterial (if not irrelevant) as long as the file can be downloaded, Dropboxed, WeTransferred, whatever. Infinite options provide for an ever-finer gradient of opinions; hence, the time these screen addicts spend watching movies is even more precious, and the stakes are paradoxically higher and lower. Some can catch a flick and appreciate its contours of imperfection, the roughshod humanity of the nonprofessional performances, the precariousness of the camerawork and the political reasons why it may have been impossible to see for decades; others will see little more than “acting could have been better; story dragged in the middle; solid 2 out of 5.” On to the next one.

So while the leveling of the playing field for thoughtful criticism continues apace, wishing in kind for a different Letterboxd would be not just naïve but ahistorical; counterproductive. It’s hard to tell if the issue is that these extremely online cinephiles are uninformed or too informed. Running these drills takes my mind in weird directions, like: who is the ideal “virgin” watcher of a movie I’m programming? How do I sell an obscure film to people without burying them in historical/cultural/aesthetic context? Or without bastardizing/obfuscating the actual experience of watching it? How will I attract the attention of people who aren’t already lost in the cinephile/Letterboxd sauce? Hopefully the movie argues for itself well enough, but you still need someone plopped down in front of it before hitting the Play button. These questions aren’t a side nuisance of programming, exhibition or distribution; answering them is the job.

Last December the British film journal Sight and Sound published their once-a-decade “Greatest Films of All Time” poll, which aggregates unranked top-ten lists from a bustling variety of respondents into a ranked megalist. This year’s edition included over 1,600 filmmakers, critics, programmers, scholars and shitposters - many more (with a much wider, uh, editorial mandate) than had participated in prior editions of the poll. The magazine continues to release individual contributors’ ballots on their website, complete with a function allowing readers to see who voted for which title, as long as the title in question made it to the top 250. Some respondents have been asked to write about films for which they were the only voters, for a “hidden gems” issue of the magazine. The major upset/triumph was Chantal Akerman’s 203-minute masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles surfacing at #1; it had been #36 in the 2012 edition, which put Vertigo in the top slot (it’s #2 in this year’s edition.) Many were disturbed by the influx of films from the last decade- specifically Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite - displacing more canonical films/directors. The shift was arguably one of demographics, and therefore, according to some vague logic, the seriousness of the poll’s results had diminished. Paul Schrader took to Facebook and called it “a politically correct rejiggering”, later clarifying, in the abattoir of a comment section, that “The notion of the Canon is based on history and if the history of film has (sic) is predominantly male and white so be it.”

I started writing criticism in 2011, but have mutated from “film critic” to “film programmer who writes” (read: troll) precisely because this “notion of the Canon” is a nuisance, a headache, the problem that galvanized most of my film-programming, and therefore adult, life. And I don’t think Paul is inaccurate describing it that way; my problem is with the implication behind his so be it. If I see “predominantly male and white” as a problem, he sees it as a monolithic fact. Schrader is not the only Baby Boomer who bemoaned the list as if it were curated from a place of ignorance, but it's hardly curated at all. My gut tells me the Boomers (and, in short order behind them, Gen-Xers) are haunted by the forewarning of future generations’ indifference to their aesthetic principles, which really sounds like, you know, the forward march of Time, if not full-on memento mori. (Indeed, much of the press around Schrader’s new Master Gardener is couched in the awareness he doesn’t have many films left in him; same goes for his most famous collaborator Martin Scorsese, whose Killers of the Flower Moon just premiered at Cannes, and whose position at the top of film culture’s Mount Olympus contrasts starkly with Schrader’s prolific cranking out of new, low-budget screenplays and implosive oversharing on Facebook. Both men4 talk openly about their careers in the context of time running out.)

When founding National Review, William F. Buckley alleged the magazine’s project was to “stand athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.” But not a few film luminaries are in fact heavily inclined to do so and, as my dear friend (and first editor) Mark Asch pointed out as we surveyed the Sight and Sound wreckage together, this yelling of “Stop!” is a losing game. It’s understandable enough: collectively held notions of history are more and more faded by viral apocrypha and brain-scrambling social media addiction, and yet my sense is that eased routes of access to old movies is driving interest in the medium in parallel. If you want film culture to, in fact, survive, then a more contemporary perspective on what constitutes “greatness” in a movie can only be a good thing. But if your concern is “legacy” and you’re a white guy born in 1946, then yes, it is a step backwards to “lose” Lawrence of Arabia to Get Out. (Put another way: for all its shameful brownface, colonial hagiography and Kennedy-era psychosexual sadism, I love Lawrence of Arabia. I’m also looking forward to films from a generation that has more use for Get Out than for Lawrence of Arabia. Am I trying to have it both ways - a post-everything, Letterboxd mentality?)

From here we can identify a tension between knowing your history and starting from zero/ripping it up/starting again. Are these views contradictory? As long as the discarded older movie in question is still available as a file on a hard drive, hope springs eternal. But that last sentiment speaks to a different and no less pernicious ignorance, the widespread, painfully false notion that everything worth preserving has been preserved, or is readily available. Anyone even casually engaged in the work of restoring or programming films which have fallen to the margins, if not “old movies” at large, will get ulcers at the suggestion. Same goes for anyone monitoring the way studios and their streaming outfits have been disappearing "content” from their services - in some cases, making it truly impossible to see a movie or show made just within the last few years. So here we stumble upon another contradiction: what if the archivists and the pirates need each other? Even if they don’t, what if they are the only two people left on the planet who still care about the movie in question? Will the last cinephile turn off the projector? Consider the words of Paolo Cherchi-Usai, in the “Ethics of Film Preservation” chapter of his book Silent Cinema: An Introduction:

A harsh truth of film culture is that audiences are often - perhaps generally - the most conservative players in the game. We want to see the masterpieces, the films that film history books have taught us to consider as cornerstones in the development of film style. We look for 'the best films ever made', we play with the lists of the 100 titles everybody should see. This immoral and nefarious exercise has become the staple of organisations whose mission should be the preservation of motion picture heritage. Its destructive consequences are obvious. Film culture becomes the equivalent of a tourist itinerary where a certain country is supposedly covered once all the main monuments have been seen. Been there, done that… Despite all the big talk about constantly rewriting the history of cinema and discussing its canons, we keep showing the same classics over and over again. One may say that younger generations have a right to see the great works we already take for granted, and that there's still a difference between a Buster Keaton of the golden years and an Eclair comedy, but that's not a valid reason to refuse them a chance to broaden their horizons. Is this what a film archive is for? A shelter for a privileged minority of cultural icons? A sanatorium for all the rest? An observatory of decomposing nitrate prints, or worse, a cemetery where archivists are paid for the sad duty of witnessing the progressive self-destruction of film history? Saving mummies of what's left, amongst the indifference of our time? Why bother spending fortunes for such an absurd task?

Back to the Greatest Film Ever Made: for me this question is only worth exploring once you’ve agreed in advance that it is, technically speaking, a waste of time. And arguably - as in, I’d get into this over pizza with my friends - Jeanne Dielman is a solid pick. Its #1 position on the Sight and Sound list is a win for both visibility and access, and should be embraced as such, because the movie was not as widely available in 2012 as it is today; although it had been re-released by Janus in 2009, streaming was not yet an option. But here are other reasons I found the anti-woke brouhaha over The List especially hard to stomach: not a single film from Latin America made it to the Top 100; Akerman is one of only nine female directors who made the cut; just seven Black filmmakers are on the list; there are just two films from Africa, one from India. (Is that not even more telltale given that Sight and Sound is a British magazine?) If a list is indeed a snapshot, or an ultrasound, of a critical sensibility at work, then this one proves there’s still a hell of a lot more canon that needs dismantling.

Perusing the results, I felt like I was still trapped in the moment of disbelief when, in 2014, Spike Lee saw fit to include Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto on the “Essential Film List” he disseminated to his NYU students. But it’s also too broad and scattered - consider the difference between 150 respondents in 2012 versus 1,600+ in 2022 - for any one takeaway to hold water. My conversation with Mark led me to realize that, despite Schrader’s vituperations, the list could have been far less conservative. If it took 31+ votes for a single film to appear in the Top 100, a smaller or more intensely cultivated list of respondents could have posed a greater “risk” to the Canon - provided, of course, they were not all white men in film culture over the age of 50. (And it’s worth mentioning, since the individual ballots have been made available to peruse, the filmmaker respondents tend to have much more interesting taste than the critics.) Put simply: it is a credit to the organizers of the poll (which included consultants outside the BFI, including the writer and theorist Girish Shambu) that seemingly everybody found something to get mad about.

In 2019, the feminist film journal Another Gaze published the panegyric “Against Lists” by film scholar Elena Gorfinkel. I recommend reading it in full and, if you’re one of those people whose blood boils especially hot at the thought of Citizen Kane slipping from #3 to #5 or whatever, try to maintain a sense of humor about it. Gorfinkel scores a number of points but this one, to my mind, is the most salient:

Lists won’t create new canons – especially not of lost women, queer, trans, Black, Latinx, global south, decolonial and anti-colonial filmmakers.

Who will ask Barbara Hammer, Kathleen Collins, Kira Muratova, and Sara Gómez for their lists?

Lists pretend to make a claim about the present and the past, but are anti-historical, obsessed with their own moment, with the narrow horizon and tyranny of contemporaneity. They consolidate and reaffirm the hidebound tastes of the already heard.

Why does this resonate with me? Probably because four different filmmakers with whom I have worked - Dore O., Gregorio Rocha, Jeff Barnaby and Carolyn Strachan - died in 2022, losses which went unnoticed by the leading lights of cinema culture. List-making reveals a natural impulse (and perhaps a desperate effort) to make sense of the past, but it gestures to the future as well: we amend the old canon (and consecrate new ones) in order to tell ourselves we are keeping up, doing a good job affirming the work, and thus the makers, we love.

But what if that’s baloney? Before Akerman’s suicide in 2015, she decried the alleged influence of Jeanne Dielman with jokes that she was still waiting to get paid, infamously asserting (on a different brutal Facebook comment thread) that she was influenced by none other than herself. Often referred to on a first-name basis by young online cinephiles who probably never met her, “Chantal” is a prime example of the unfortunate tendency whereby dead artists kick up a lot more sympathy - and interest - than they did in life: restorations, re-releases, retrospectives, memoirs, merchandise. After her death, the New York Times had the gall to suggest Akerman’s (lifelong, well-documented) depression had been triggered by some stray boos at Cannes after the press screening of her eviscerating last film, No Home Movie - prompting Dennis Lim, now Artistic Director of the New York Film Festival, to take to Facebook: “I assure you, she did not give a shit about your fucking boos.”

These memories resurfaced after the Sight and Sound drop. I was intrigued that the magazine’s Managing Editor Isabel Stevens contextualized the rollout of the list by sharing an email exchange she had with Akerman in 2014: Triumphal? Apologetic? Too soon? Too late? Just right?

I’m obsessed with counterfactual, woulda-shoulda-mighta-been alternate film histories, in some cases hinging on details tiny or otherwise which, I tell myself, would have changed everything: Sergei Eisenstein convincing Paramount to adapt Capital. Gone With the Wind climaxing with Rhett saying “Frankly my dear, it makes my gorge rise” instead of “I don’t give a damn”. After Hours directed by Tim Burton instead of Martin Scorsese. Little Shop of Horrors ending with Seymour and the plant aliens killing everybody on earth instead of the happy theatrical ending. Coolio playing Scarecrow in Joel Schumacher’s third Batman sequel. Superman Lives. Hype Williams making Speed Racer in 2000 instead of the Wachowskis in 2008. The Break-Up ending with an actual break-up. The aborted Jack Nicholson/Kirsten Wiig remake of Toni Erdmann. It goes on. And I have written before about cinephilia as a form of conspiratorial thinking, of drawing feverish connections between possibly (almost guaranteedly) unrelated things.

But as a programmer, I’m generally saying the best (of the past) is yet to come. But sometimes in curatorial work, I find myself asking: “Why has no one done this before?!” and, sooner or later it turns out there is in fact a reason.

In the summer of 2021 I began fixating on an unfinished Chantal Akerman film called Hangin’ Out Yonkers, a portrait of teenage drug addicts and sex workers who were enrolled in a “citywide drug prevention and treatment program” called R.A.P. (Retention And Prevention); Akerman had shot the material while living in New York in 1972. Here is how she described the film in an interview with Jacqueline Aubenas, in 1995:

They were there every noon, in the open house, others who had more advanced drug problems had to take care of themselves. I had filmed everything they did at home and had hundreds of hours of interviews. I wanted to add vocals, but I lost the reels... and besides, there was no negative. The Cinémathèque de Bélgique must have what was saved from all that. I stayed with them for three or four months. I looked, I listened. There was very little money to make it. There was no synchronous sound. In the images you could see them living, playing billiards... The image was very expressive, very strong. They were 12, 14 years old, they were Black or Italian. The girls were already prostituting themselves to get their fix. It was surprising and exciting. I did a first cut and then I dedicated myself to something else. When, later, in the post-Nixon period, I wanted to resume it, to continue filming, (the government) had suppressed this social assistance. At the time it was very innovative and courageous. Now, this subject has become fashionable, but in 1972 nobody talked about it. It happened elsewhere, at the end of the world. I took the subway. I took a long subway ride every day. The journey by subway was very interesting in itself, it crossed all layers of the population. And then I'd get there and listen, and watch.

I emailed the Fondation Akerman to ask about what extant materials they had. Below is what Celine Brouwez, at the Fondation, sent me back:

All is left from Hangin’ Out Yonkers is one reel (image, the sound is lost) corresponding to roughly half of the film (which was never fully finished, cut, mixed, etc.) We preserve what remains of the film, and we are always hopeful to find what is missing (sound and the other half.) Under these circumstances, we tend to discourage screening something that is really not representative of what the project was meant to be. The film is very rarely seen in integral retrospectives, but that’s all.

I was allowed a private link to view the footage. Immediately, I was stricken by the sharp geometry of the camera angles, the alternately dingy and saturated color palette and the flat, self-conscious (Brechtian?) framing of the teenage participants5. In this footage, I wanted to believe I would find some missing link (an “element X”) between Hangin’ Out Yonkers and Akerman’s later works - Jeanne Dielman for sure, as it was made directly after the Yonkers project fell apart - but also her formalist nonfiction work from the same era ,the contemporaneous silent documentary Hôtel Monterey and the confessional essay film News From Home completed in 1977. Without sound or dialogue, the material only deepened the mystery; there was no easy relief map for what Akerman had hoped to do with this film, whatever the aesthetic similarities with her later works.

I kept digging and found the names of some people who were in the mix of Akerman’s life during this period. They sounded like a hip girl gang, maybe like a more political claque than the wandering twentysomethings depicted in Claudia Weill’s classic Girlfriends. I had to learn more. I dug around on Facebook, LinkedIn, JSTOR. I cold-called a nonprofit organization and found a means of contacting the woman who had been program director at the R.A.P. drop-in center. She and I spoke for about an hour and a half on the phone. She told me she had managed one of two different R.A.P. centers in Yonkers at that time, that the project was underwritten by city funds, and that she was managing the center with her husband, who would die at a tragically young age a few years later. She told me the bulk of the Yonkers material had been lost, somewhere, on a train in Europe; that she had paid for the production of Hangin’ Out Yonkers and that she and Akerman joked that she was “owed” another film after the reels went missing. (Was she upset with Akerman for losing a film she had paid for? Not at all, she stressed - they were friends above all else.) I asked if it might be possible to find the participants and interview them about their experiences with Akerman; she hedged. And if I did - would they even remember much from the shoot?

She emphasized that Akerman’s R.A.P. visitations were fun for the kids, but the shooting of what would have become Hangin’ Out Yonkers was just one of many activities attempted at the drop-in center, most of them diversionary in nature. She told me Akerman returned to Yonkers in the 1980s and took interest in a local woman - a source of inspiration for the second attempt at Hangin’ Out Yonkers. I guess Akerman had begun conducting interviews and shooting ¾-inch tape out the window of the Metro North train, but ultimately nothing came of the new project. All told, her friend didn’t sound displeased to blow the dust off these memories, and offered the contact information of another friend, who had uploaded an album with wonderfully evocative black-and-white photos from those days to Facebook shortly after Akerman’s death. I emailed, and eventually that friend got back to me:

Dear Steve,

I do not want to participate in another project about Chantal.

There have been so many books, articles and tributes since her death, each interview damages the original memory a little bit. Chantal and I were close friends. Each time there is another discussion, another little piece of a memory is lost in the repetition. Something is fabricated in an attempt to tell a more coherent story. I hope you understand this. I wish you the best of luck.

The email was economical without being terse, emotional without being sentimental. Unsure how to feel, I relayed her message to the earlier friend, who replied:

I appreciate you sharing her response. I think it is beautifully said. I think she is honest and correct too. It is really not coherent to either of us, more like images and memories that we both cherish and would rather leave alone.

Here I found a kind of corroboration of Gorfinkel’s Against Lists. Being one big invention, history needs constant revising; but whatever the results of my “attempt to tell a more coherent story”, they could not benefit Chantal Akerman or, indeed, these women whose names I have (hopefully obviously) withheld. My research was doubling back on itself; the wisdom I received from one friend dissuaded the other from sharing further with me, and I could push no more. I wanted to enrich my appreciation for the development of Akerman’s signature style, which is fine - but I was becoming a nuisance. I could have just watched more Akerman films on the Criterion Channel, so I did.

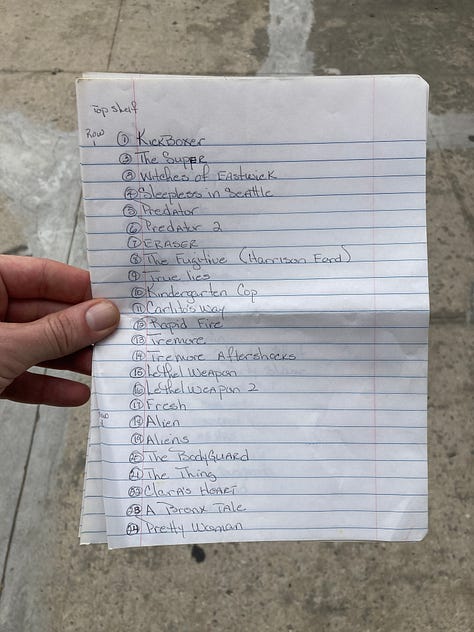

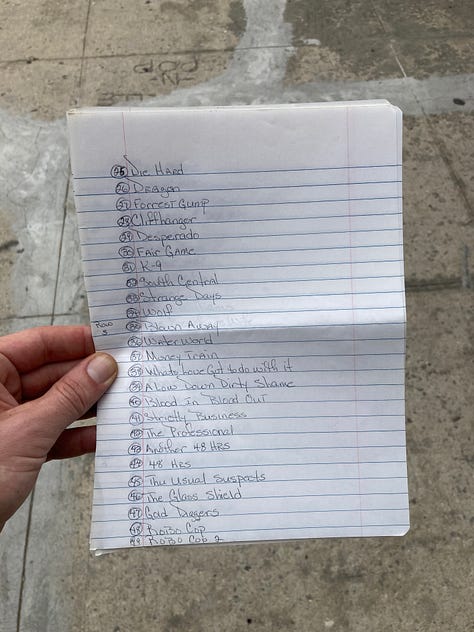

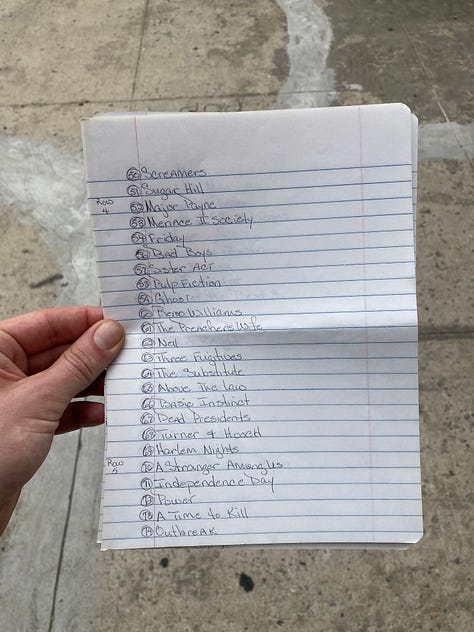

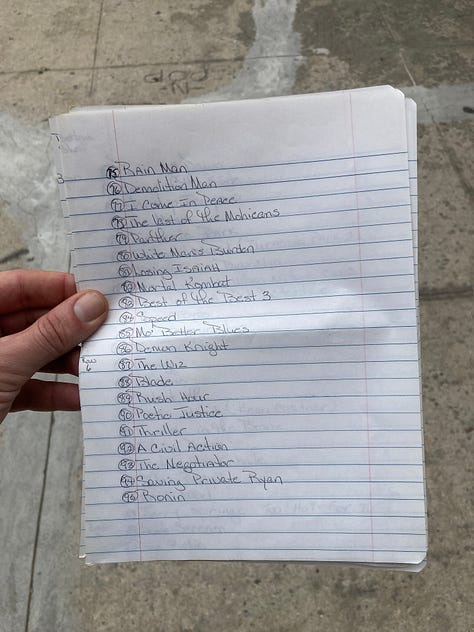

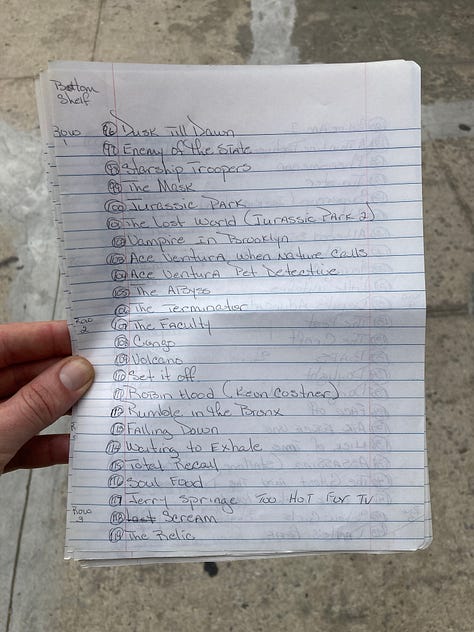

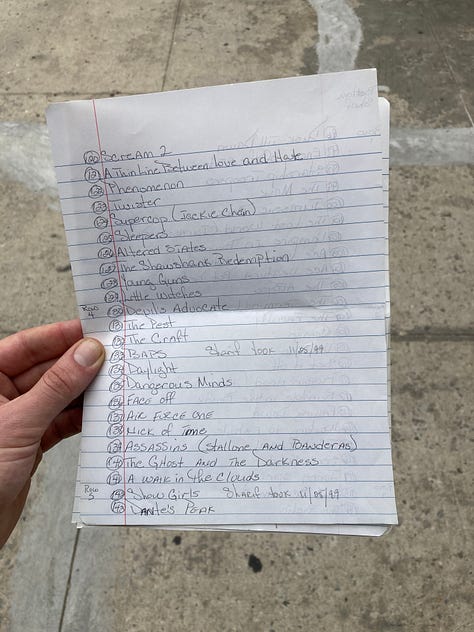

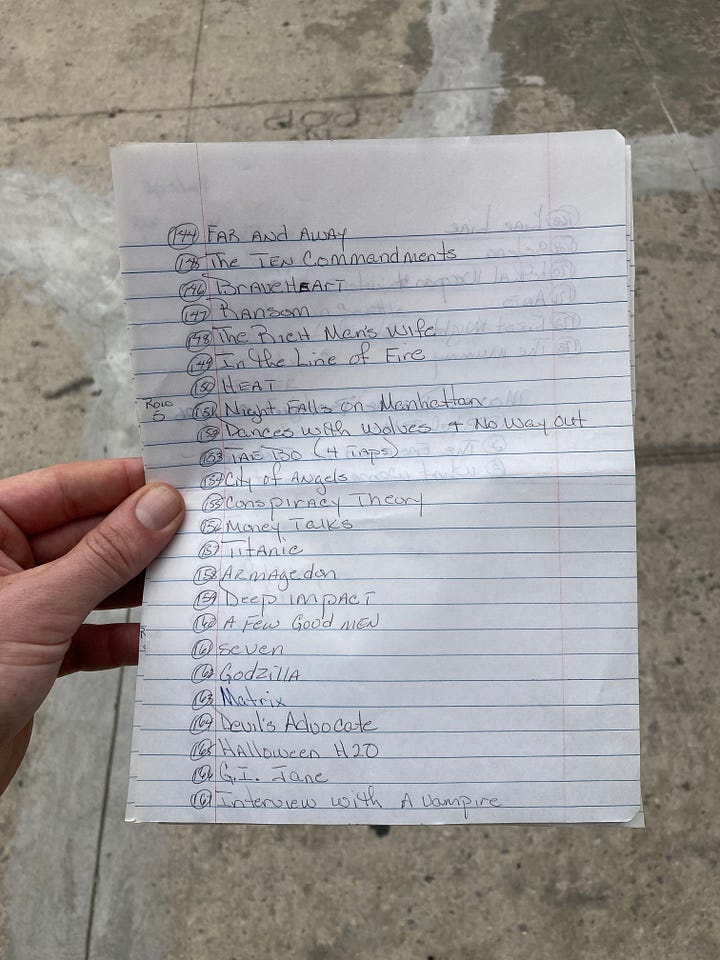

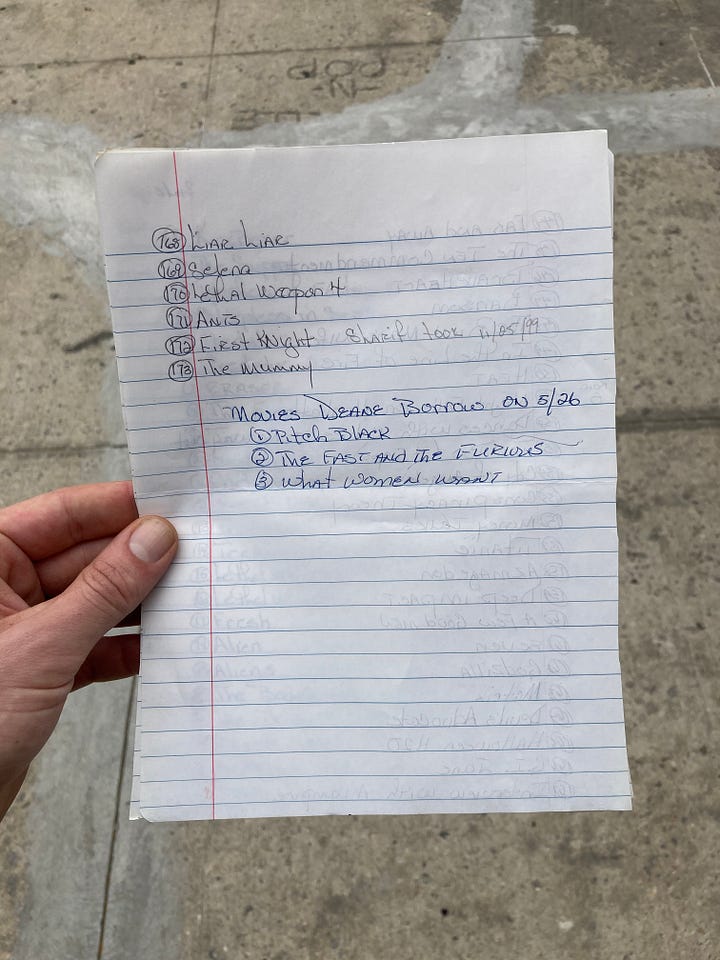

That same summer, I stumbled upon one of the most moving (and possibly saddest?) things I ever encountered on a New York City sidewalk: a pair of large cardboard boxes laid out on Bushwick Avenue, each containing a mound of well-loved VHS tapes. A mountain of de-accessioned VHS on the sidewalk is no big deal, but this one had four pieces of paper neatly folded on top:

Clearly this was a home video collection rather than a list of the greatest films ever made, but it’s not hard to imagine it was somebody’s Library of Alexandria not so long ago. It’s a 176-title mosaic, a portrait of the era when studios pulled serious cash from consumers (a great many of them, we can surmise, fathers) curating their dream home video archives (“1. Kickboxer”). The end-of-history energy is tremendous. (Would The Shawshank Redemption even be on the IMDB Top 250 if not for the VHS boom?) The titles towards the end foretell the imminent digital revolution, typically embodied by the first film to sell over a million DVD units, The Matrix - included here, among other Y2K-era hits like What Women Want and The Fast and the Furious. But mostly it was a capsule from a time that felt recent yet, given the lack of movie-watching options available to the unnamed curator here, utterly alien. I smiled at paired titles like Rain Man beside Demolition Man, Armageddon beside Deep Impact. But even if I understood putting the tapes out on the sidewalk to make space in one’s home, the inclusion of the list (the catalog? the inventory?) added a darker dimension - it was either forgotten or discarded on purpose. Probably, someone died. Another mystery I would never get a chance to solve.

I remembered reading about Newsweek critic David Ansen’s obsessive-compulsive system for reviewing movies as a child. (In a 2009 New York Times interview with Dennis Lim, Akerman aligned Jeanne Dielman with her childhood in postwar Brussels, describing “life organized by rituals”.) Karen Lamassonne, long-time partner of Colombian filmmaker Luis Ospina, told me he kept boxes of pocket-sized booklets where he logged the title of every movie he ever saw. The list reminded me of my earliest film freak years in turn-of-the-millennium Seattle, studiously listing movies I needed to rent until the titles had crowded every square millimeter of the page. (Recall Morgan Freeman in Se7en: “No dates. Placed on the shelves in no discernible order. Just his mind, poured out on paper.”) These were all regular behaviors of pre-digital age cinephiles, but I guess the difference is most of them were kept private. To me Letterboxd feels like so much else of the online uncanny: an externalizing of passions and appetites thought inconceivable (and ill-advised!) not long ago at all.

Back to 2023 for one final bit of oversharing. Last month saw the untimely death of Jim Gabriel, a film enthusiast I met on Twitter about a decade ago. Jim had worked in The Biz back in the ‘90s and fallen on harder times in the more recent past; his prolific Twitter testified to an insatiable mind, geeking out over new releases while offering inimitable appreciations of old ones - canonical titles for sure, but Jim also had a sharp attention to film artists who were overlooked or underappreciated. (Caden Mark Gardner, a critic and one of a great many younger writers championed by Jim, wrote a beautiful tribute that gives a sense of his personal canon.) Jim and I connected in person when I visited Chicago in 2018; I was touring a series of films by Raymundo Gleyzer at the Block Museum at Northwestern, and Jim came to all three programs. He was something of a Surrealist, pro-rock n’ roll, pro-drug; he understood that reality was Bad, but also never failed to find grace notes and absurd screwball ironies in otherwise lamentable situations, including his own. (Even if Master Gardener sucked, it makes me terribly sad to realize Jim will never lay eyes on Killers of the Flower Moon.)

Right now the biggest repository of Jim’s thoughts is probably his still-online Twitter account, which I hope some of his acolytes scan and screenshot for gems before it gets removed for being inactive. If you click through, you’ll see that Jim spent a lot of time in dire straits, but also that he knew how to spin a phrase and took real pleasure in doing so. Movies, and talking about them, was a form of solace. Jim was an even more reluctant Letterboxd user than me (his bio reads “Yes, movies are terrible”) but no dilettante when it came to writing on film; just a quick sampling of his criticism will set your brain on fire. He contributed to the Chicago-based film listing Cine-File, and I hope his capsule writeups are aggregated soon. One thing that stuck out to me was the kicker from his review of the long-impossible-to-see concert documentary Prince: Sign O’ The Times:

There’ll be no more displays of that munificent talent and giant heart, but screenings like this afford opportunities to commune with each other, and with that spirit and body equalized by pain, to love anew the will and wit and sexy, churchy funk of it all. And if that seems overly sentimental, I would submit that a life given over to art that doesn’t contain a measure of sentiment is worth less than nothing; you might as well take up solitaire.

My poking-around inevitably led me to Jim’s blog Half a Ballon, sporadically updated but further evidence of a holy fool’s brilliant movie-mind. Jim would kill me for saying this, but François Truffaut is not a filmmaker I spend a lot of time thinking about - but I was stopped in my tracks by a post soberly reflecting on Truffaut’s life being cut short. There, I found the words from Jim to sew it all together:

One might think that mourning for films that will never be made is a base sentiment, but what is mourning if not the selfish wish for a sensation you’ll never have again?

Anyway, here are my top ten films of all time.

(This is actually ten shorts and ten features. Drag me…)

Features

Strike! (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

M. (Fritz Lang, 1930)

Only Angels Have Wings (Howard Hawks, 1939)

Èl (Luis Buñuel, 1953)

Play Time (Jacques Tati, 1967)

One Way or Another (Sara Gomez, 1974)

The Ascent (Larissa Shepitko, 1977)

Twenty Years Later: A Man Marked for Death (Eduardo Coutinho, 1980)

Personal Problems (Bill Gunn, 1982)

Ran (Kurosawa Akira, 1985)

Shorts

Ballet Mécanique (Dudley Murphey & Fernand Léger, 1924)

Popeye the Sailor Meets Sinbad the Sailor (Max and Dave Fleischer, 1937)

Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren and Alexandr Hackenschmied, 1943)

Blood of the Beasts (Georges Franju, 1949)

La Jetee (Chris Marker, 1962)

The House is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1962)

Now! (Santiago Alvarez, 1965)

Vampires of Poverty (Luis Ospina & Carlos Mayolo, 1976)

Spacy (Takashi Ito, 1981)

World of Glory (Roy Andersson, 1991)

Special thanks to Mark Asch, Tayler Montague, Alexandra Coburn, Matt Peterson and Dee Dee Halleck.

Current Mood: Serene 😌

Current Music: Fleetwood Mac - Albatross

Funny enough, introduction to Slant - the reason it was an honor to write for Slant - was their 2003 Essential Films list, a spirited rejoinder to the AFI 100 Films list published five years earlier. Slant was reviewing the AFI’s review: a century’s worth of movies wrongly (in their view) considered minor works by major directors, and/or major works by major directors that had been treated as minor-at-the-time by their attendant studios. Watching them come out on DVD in the subsequent years was a sweet relief, and formed a kind of spine upon which to build my own personal canon - not that I agreed with every choice, obviously.

Ed Gonzalez’ rigorous system for balloting Slant contributors should be the stuff of legend, and hopefully some day it will be… This is the main reason I participated in Slant’s top ten lists even as I grew more skeptical of numbered ranking; here you can see my ballots for 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017. Friends and colleagues would be surprised to see me include a movie I hadn’t reviewed; for me, it took a while to realize that sometimes, the highest compliment you can pay a transcendent artwork is to not write about it.

Riding the subway last fall I saw a passenger watching what appeared to be a big-budget movie on their phone, subtitled in Arabic; I recognized the stars (Mark Wahlberg, Antonio Banderas) but not the film itself. It was called Uncharted, and it would be released in theaters weeks later.